In

1873 Jessie made his first trip west to California, with Willoughby

Cole, the son of United States Senator Cornelius Cole. In San

Francisco Mrs. Cole told him several children's parties were arranged.

The prospect of parties frightened Jesse, a regular trait. Mrs.

Cole, apparently sensitive to this, canceled and declined invitations

on his behalf. When he got back to Washington, however, parties

intruded on his life in another way.

In

1873 Jessie made his first trip west to California, with Willoughby

Cole, the son of United States Senator Cornelius Cole. In San

Francisco Mrs. Cole told him several children's parties were arranged.

The prospect of parties frightened Jesse, a regular trait. Mrs.

Cole, apparently sensitive to this, canceled and declined invitations

on his behalf. When he got back to Washington, however, parties

intruded on his life in another way.

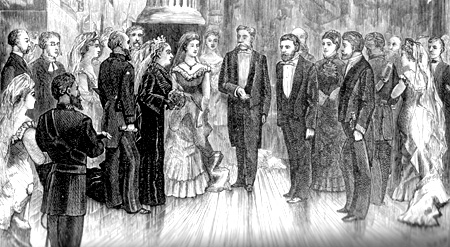

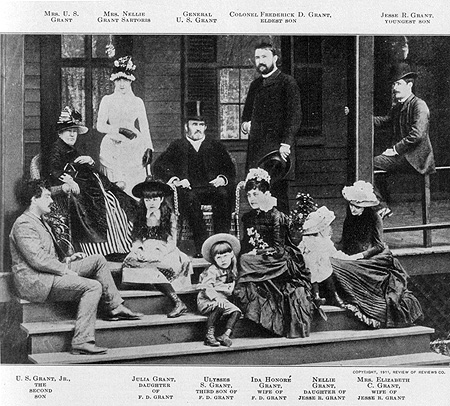

Nellie and Jesse Grant c. 1870

His sister Ellen - "Nellie" - just two years older

than Jessie, was a party girl. Mother Julie indulged Nellie's

partying, but being of Southern stock, Julia had strict notions

about chivalry. It was "unthinkable" for Nellie to go

out in the evening, no matter where or with whom, unless accompanied

by a male family member. Both older brothers Frederick and Ulysses

Jr. being away at West Point and Harvard, respectively, the only

available male family was Jesse. Nellie had to party with her

younger brother as escort. Both disliked it, besides which Jesse

was afraid of girls.

Jesse's and Nellie's formal educations lurched along. Nellie was

sent to a good girls' boarding school in Connecticut. In just

one hour she sent her parents three telegrams saying she would

die if she had to stay there. A White House aide brought her back.

About a year later Jesse was sent to boarding school in Cheltenham,

near Philadelphia. After a few months he also wrote that he wanted

to come back to the White House. Grant had him return immediately.

Jessie made another trip to California in 1874. In the Midwest

he linked up with his oldest brother Frederick Dent Grant. Frederick

married shortly afterwards, but the marriage that really got attention

was Nellie's. At age 17 she met an aristocratic Englishman, Algernon

Sartoris. When it became obvious that the two were considering

marriage, President Grant worried that Nellie was too young, and

he knew nothing about Sartoris. Nonetheless in 1874 Nellie and

Algernon were married in an elaborate ceremony in the White House

East Room. Grant was seen afterwards on his bed crying. Nellie

was going to England and he would miss her terribly. "Nellie

was gone," said Jesse, "the White House strangely empty."

In

spite of Jesse's erratic education, he entered Cornell University

in the autumn of 1874, aged under 17. Two years later, 1876, there

was talk of nominating President Grant for a third term. Grant

refused to have his name presented at the Republican Convention.

The campaign that followed resulted in the most bitterly contested

presidential election in history, with Republican candidate Rutherford

Hayes being declared the winner by the House of Representatives

even though his Democratic opponent had outpolled him by 250,000

popular votes.

In

spite of Jesse's erratic education, he entered Cornell University

in the autumn of 1874, aged under 17. Two years later, 1876, there

was talk of nominating President Grant for a third term. Grant

refused to have his name presented at the Republican Convention.

The campaign that followed resulted in the most bitterly contested

presidential election in history, with Republican candidate Rutherford

Hayes being declared the winner by the House of Representatives

even though his Democratic opponent had outpolled him by 250,000

popular votes.

Jesse Root Grant in his early twenties

Hayes's accession to the presidency, and one undistinguished term,

brought relief to Grant. He had saved $15,000 on which to take

a trip around the world as long as the money lasted. Jesse dropped

out of Cornell, and on May 17, 1877 sailed with his parents on

the Indiana. After a rough but uneventful voyage they arrived

in Liverpool.

Expecting only local American representatives to receive them,

the three Grants found the harbor bedecked with flags and the

Lord Mayor and prominent citizens at the dock. The pattern continued

through the British Isles and afterwards. Crowds and honors greeted

Grant in Manchester, Sheffield, and Leicester; workmen got a half-holiday

on his arrival.

There was a month in London of almost continuous entertainment.

Try as Jesse would, he could not escape all the dinners and receptions.

They saw Nellie at her home in Southampton, went back to London,

where Jesse's remark about attending so many events got him unfavorable

mention in the newspapers, and were about to leave when they got

the ultimate invitation to see Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle.

Victoria had been withdrawn ever since the untimely death of

her husband Prince Albert in 1861. The Grants were met at Windsor

by Master of the Household Sir John Cowell, who explained that

Her Majesty was out driving and would receive them later. As Jesse

was dressing for dinner, Sir John appeared. Her Majesty was indisposed,

he said. "Large gatherings, particularly at dinner, bring

on a most distressing vertigo. As a consequence of this deplorable

condition it has been decided that only those who must be present

are to dine with Her Majesty." Jesse would dine with the

household and would be presented to Her Majesty afterwards. The

newspapers would suggest that he had dined with the Queen.

Jesse was not amused. "It would appear that I can have all

the honor by report, and avoid even the tedium of dining with

the Household, by quickly leaving for London." His reaction

practically provoked a diplomatic crisis. "A tremendous scandal

would result," said Sir John, if the newspapers heard of

it. Jesse said he wouldn't tell them the Queen decided he was

only fit to eat with the help. "You do not understand,"

gasped Sir John. "Queen's Household are nobility." Assured

he could not leave, Jesse said "Just watch me," and

began packing. Sir John pleaded with Jesse to understand the foibles

of an old lady - Victoria - in ill health, which only convinced

Jesse that Victoria herself objected to his presence.

Sir John brought the American minister, who said he would tell

Jesse's father about his conduct. Jesse agreed to do whatever

Grant Sr. wanted. Grant said that in Jesse's place he would do

as he did. The crisis was finally averted when Sir John appeared

as Jesse was about to walk back to the train station and announced

that Her Gracious Majesty would be pleased to have Jesse at dinner.

After dinner and billiards Jesse returned to his quarters to find

Sir John with a bottle of brandy. Sir John told him about life

at Windsor. It seemed Victoria was always indisposed when a visitor

arrived, but the newspapers were always told things had proceeded

as planned. The brandy bottle was almost empty by morning.

Receptions and honors for General Grant and family continued on

the Continent, when they went to Scotland, and on the Continent

again. The Grants were at the Paris Exposition in May, 1878, when

oldest son Fred joined them. Jesse crossed the Atlantic back home,

to enter Columbia Law School in the fall. General and Mrs. Grant

continued east, through Suez, India, China, and Japan.

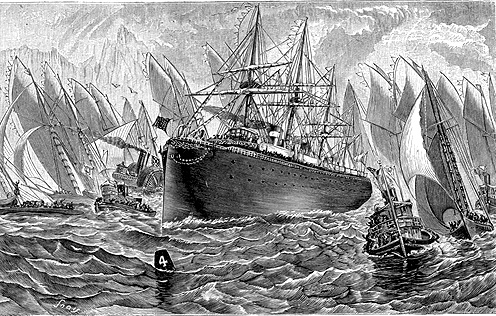

After

yet another round of receptions and dinners in Japan, and meeting

the emperor, General and Mrs. Grant boarded the steamer City of

Tokio in September 1879 to cross the Pacific.

After

yet another round of receptions and dinners in Japan, and meeting

the emperor, General and Mrs. Grant boarded the steamer City of

Tokio in September 1879 to cross the Pacific.

Grant in China, 1879

When the Grants arrived in San Francisco on September 20th, their

reception surpassed anything ever given an American anywhere in

the United States. Jesse had crossed the continent to meet them,

linking up with older brother Ulysses Jr. ("Buck"),

out from New York. They took ship through the Golden Gate with

a reception committee and boarded the Tokio.

It passed into San Francisco Bay seen, it seemed, by every citizen

in and around the city. "Telegraph Hill was a living mass

of human bodies," wrote a biographer, "and the heights

beyond…and every pier head were covered with spectators."

After the vessel docked, spectators packed Market to see the Grants

and their party drive to the Palace Hotel. Snatching a moment

alone with Jesse, Julia asked him not to notice if Grant's speech

seemed strange; a servant on board ship had accidentally thrown

his dental plate with two front teeth overboard, and he frequently

whistled.

The Grants journeyed inland to Yosemite and returned to San Francisco

for another round of receptions and banquets. During their stay

it was rumored that Buck had become enamored of Jennie Flood,

daughter of silver millionaire James Flood. If so, nothing came

of it. In November 1880 Buck married Fannie Chaffee, daughter

of Colorado Senator Jerome Chaffee, in New York City.

Jesse, however, seems to have formed a connection in San Francisco

in 1879. He never gave details, but it is probable that at that

time he met Elizabeth Chapman, daughter of San Francisco real

estate figure William S. Chapman. They were married in San Francisco

in September 1880.

Julia

had tired of traveling and was ready to return home in 1879. Grant

would have liked to see Australia, which would have meant traveling

another six months and returning in spring, 1880. His political

associates would also have preferred that. They were planning

to get nominate Grant for a third term as president, and the timing

of his return would have been better.

Julia

had tired of traveling and was ready to return home in 1879. Grant

would have liked to see Australia, which would have meant traveling

another six months and returning in spring, 1880. His political

associates would also have preferred that. They were planning

to get nominate Grant for a third term as president, and the timing

of his return would have been better.

In San Francisco Jesse discussed the third term with Grant, who

dreaded it, but would accept it. He made no efforts on his own

behalf. His supporters, called "stalwarts" for their

opposition to Civil Service reform, entered him at the 1880 Republican

National Convention in Chicago. After multiple ballots the party

nominated reform candidate James Garfield. Garfield won election

narrowly, but six months after his inauguration he was shot by

a disaffected stalwart. After lingering months, he died and was

succeeded by Vice-President Chester A. Arthur.

Grant had spent most of his money in his world trip, but a lucky

investment in Nevada Silver mines yielded several thousand dollars.

Buck had a profitable law practice in New York City, and had met

a Wall Street investor named Ferdinand Ward, with whom he went

into partnership. General Grant and Buck invested practically

all they had in the firm, which paid handsome dividends - too

handsome. In spring 1884 the firm was besieged by unpaid creditors.

Ferdinand Ward was the 1880's equivalent of Bernard Madoff, and

had run what would nowadays be called a Ponzi scheme. The firm

collapsed and Ward went to prison. General Grant at 62 was without

income and had only a few hundred dollars.

About the same time Grant had unpleasant sensations in his throat.

Reluctantly seeing a doctor, he learned that he had epithelial

cancer, a death sentence. A professional soldier who saw thousand

of men die, Grant was less concerned for himself than for Julia,

who would be left destitute. Mark Twain, whom he had known for

several years, urged Grant to write his memoirs and Twain would

publish them.

The

pains in his throat made dictating impossible for Grant, but he

wrote at a pace that would be remarkable for anyone and is amazing

for someone with a terminal illness. Grant had written a few articles

for the Century magazine, but no one had ever considered him a

literary man. His style was direct and vastly more readable than

the overblown writings of most public figures in the Victorian

era. His memoirs would rank among the best accounts by a military

man since the Commentaries of Julius Caesar.

The

pains in his throat made dictating impossible for Grant, but he

wrote at a pace that would be remarkable for anyone and is amazing

for someone with a terminal illness. Grant had written a few articles

for the Century magazine, but no one had ever considered him a

literary man. His style was direct and vastly more readable than

the overblown writings of most public figures in the Victorian

era. His memoirs would rank among the best accounts by a military

man since the Commentaries of Julius Caesar.

Grant, very ill, writes his memoirs.

The family moved Grant to a house at Mount McGregor in the Adirondacks

Mountains of New York State. Jesse, his wife Elizabeth, and their

daughter Nellie came, along with the other sons, their families,

and Grant's daughter Nellie. Grant's misgivings about her marriage

had been born out. Algernon Sartoris was a heavy drinker and philanderer,

and died after the birth of their fourth child. Nellie returned

to the United States, but being the wife of a British subject

she had lost her citizenship and had to petition Congress to restore

it.

With his family gathered around him, Grant wrote in the mornings.

Jesse's wife Elizabeth would read back to him in the afternoons,

while Grant made notes and corrections. The memoirs were finished

in June, 1885. On July 23rd, Ulysses S. Grant died. His funeral

was the largest in New York City's history. The memoirs would

give Julia over $400,000 in royalties.

Jesse had dropped out of Columbia Law School after only a year,

in fact he apparently never took a degree from any higher learning

institution. Having somehow learned about mining, he became a

free-lance mining engineer and was apparently successful. In 1888

he was in Mexico, leaving Elizabeth, daughter Nellie, and son

Chapman settled in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 1889 they lived

in Alameda. By 1893 they had leased a house in Piedmont, the upscale

East Bay suburb, but did not stay long.

Buck's

wife in New York had health problems, and he moved his family

to San Diego for its congenial climate.

Buck's

wife in New York had health problems, and he moved his family

to San Diego for its congenial climate.

Buck Grant, Jesse's older brother, in California c. 1900

In October, 1893 Jesse and his family also moved to San Diego,

where they rented a cottage on First Street. They bought a lot

at Sixth and Quince streets and built a two-story colonial-style

home for between five and six thousand dollars. Julia would come

out during the winters, and stay either with Jesse, Buck, or Nellie,

who had moved to Santa Barbara.

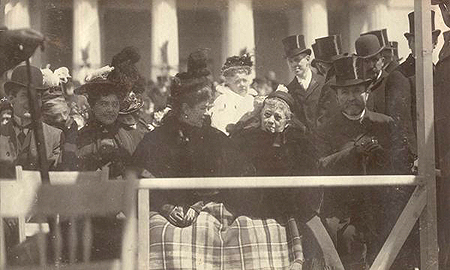

A huge crowd at the dedication of Grant's Tomb.

In 1897 the Grant family reunited for the dedication of General

Grant's tomb on Riverside Drive, New York City. General Grant's

remains were moved from a temporary vault to a massive neoclassical

structure that was and is one of the most conspicuous on the city's

west side. A huge crowd heard speeches by former President Grover

Cleveland and President William McKinley.

The family sat on the front row of the speaker's stand. Jesse

is at far left, unfortunately obscured by somebody's umbrella,

wife Elizabeth next to him. Nellie is next to her mother Julia.

The bearded man is probably the oldest son Frederick Dent Grant,

although he may be Ulysses Jr.

Julia died in 1902 and was entombed next to her husband.

In San Diego, Jesse's and Buck's real estate ventures were profitable.

Buck made one attempt at politics, running for the United States

Senate in 1904 and losing. Jesse was rootless, never staying in

one place long, leaving his wife and children.

In 1907 he tried politics himself, making a tour through Texas,

Louisiana and the southwest, sounding out support for a candidacy

for President of the United States on the Democratic ticket. On

March 5, 1908 the New York Times reported that Jesse would challenge

two-time candidate William Jennings Bryan for the Democratic nomination.

You may ask, what were Jesse Grant's qualifications for the presidency?

Good question! The Times reporter was plainly unimpressed with

Jesse's chances, and his candidacy was practically ignored.

Bryan was nominated for the third time, and lost for the third

time, to Theodore Roosevelt's successor William Howard Taft. Jesse

ventured into politics indirectly in 1912 by endorsing Democratic

candidate Woodrow Wilson. Speaking from his home in New York in

October, he compared the issues facing the country with those

in 1860 when the country split over the slavery issue and made

his father's career.

"As a son of the soldier who fought to uphold the principles

for which Abraham Lincoln stood and as a son of a Republican president,

I can see only one duty for myself - to give heartily my influence

and my vote for principle and not for the name of a party long

since divorced from its sympathy for the common man. Verily, I

believe that the principles for which Woodrow Wilson is fighting

are the principles for which my father fought, and that he (Wilson)

alone among the presidential candidates measures up to the standards

of courage, conscience and capacity of the leader whose hand my

father helped to uphold."

Jesse's vote may have counted, but his influence would not: the

Republican Party had split between incumbent Taft and third-party

candidate Theodore Roosevelt, and Wilson won easily.

Jesse made headlines again in 1913. On July 23rd, in Goldfield,

Nevada, where he had lived over six months, he filed for divorce

against his wife of 33 years on grounds of desertion. The suit

came as a surprise to Elizabeth, then living in San Francisco

with her son Chapman and mother at 3701 Washington Street in Pacific

Heights.

"This is the first information I have received regarding

the divorce action taken by my husband. I am surprised that he

should have charged me with desertion. I have never left my children

nor my home, except to go with him. If there has been any desertion

it is then on his part.

"You might say that the separation dates almost from the

time of our marriage…since which time he has been away on

mining business in many parts of the world. I have gone with him

to Mexico, to New York and to many different places where he has

had business interests, leading a nomadic existence…

"Mr. Grant has known that I was here. He has not seen fit

to come here. It has been two years since have seen him."

Jesse's case rested on a letter written him by Elizabeth from

San Diego in 1910. "I shall always treat you with respect

as long as you never come nearer me than you are at this minute

(Jesse was in New York)… The world is much more beautiful

to me seen without the black veil of misery and hopelessness in

which I last lived for a greater part of the last twenty-eight

years. Through all the years we had a home in San Diego you spent

the greater part in New York and my mother…has come to live

with me in a tiny apartment.

"Four years ago, when I went East, you had an opportunity

to reform, but did not choose to take advantage of it… I

am no more to you than any of the other women you have thrown

over, so please drop the subject and try to live without scandal

on your father's account."

The suit failed in March, 1914 when a Goldfield, Nevada judge

ruled against Jesse. Under the ruling Elizabeth continued to share

in a $5,000 annuity and community property. The following June,

1914 Jesse asked Elizabeth to return to him in New York. She refused.

In 1915 the supreme court of New York State granted Elizabeth's

application for alimony, to continue until either party's death

or divorce. Jesse tried divorce again.

In August, 1918 he got a Nevada divorce, uncontested by Elizabeth.

One week later in New York, 60-year-old Jesse married 41-year-old

Mrs. Lillian Burns Wilkins, a widow of Inwood, New York. The couple's

residence may have been in the east, but in 1924 Lillian died.

Jesse took up the final residence of his peripatetic life, probably

just after Lillian's death. For unclear reasons, possibly the

cheap land and the climate, he came to Los Altos. The 1930 census

and 1926 voter registration list show his address at P.O. Box

296, Fremont Road. Apparently wanting to leave memoirs like his

father, Jesse wrote a biography Days of My Father General Grant,

co-written by Henry Granger. Days covers Jesse's memories

of the Vicksburg campaign, to 1880 when Grant failed re-nomination

for the presidency. It was published in 1925 by Harper and Brothers.

The lists also show Kathryn Nielsen, born Pennsylvania 1888, occupation

"housekeeper," P.O. Box 296, Fremont Road. Kathryn Nielsen

was more than Jesse's housekeeper. In 1930 they bought a hillside

lot and built a home at a cost of $5,663.00. A deed of trust confirms

joint ownership by Jesse and Ms. Nielsen.The house, like so many

others on the Peninsula, is in Mission Revival style, rambling

and livable

.

.

Jesse Grant's, Los Altos Hills

Grant house, right side

Somehow it got the name Five Oaks, although there are now only

four oaks and a stump on the property. Jesse Grant lived there

only four years.

On

June 8, 1934 he died. In death as in life, he was "General

Grant's son."

On

June 8, 1934 he died. In death as in life, he was "General

Grant's son."

The Palo Alto Times reported "U.S. GRANT'S SON DIES

AT LOS ALTOS." The Chronicle reported "Grant's Last

Child Expires." His three siblings had predeceased him.

Oakland Tribune, June 9, 1934, reports "Pres. Grant's

Son Stricken."

Other papers had similar accounts, always U.S. Grant's son.

Jesse's status regarding General Grant being "dependent,"

he was interred at the National Cemetery at the Presidio of San

Francisco.

Kathryn married a local realtor, Lawrence Whitham. After her

death in 1944 the house was sold and has had had three owners

since. It has been modified, but the house and grounds retain

the peacefulness that must have appealed to the restless man who

spent the last years of his life there.

Jesse Grant's grave, National Cemetery, Presidio of San Francisco.

Photos of the house and grave by John &

Lana Ralston